Ever wondered what’s happening in the brain when you make a decision? Now, my brain will try to explain to your brain what’s happening in our brains.

If you’re someone who’s never struggled with indecision in your life, then you can perchance decisively stop reading here. Otherwise, if you find yourself torn between staying and leaving, then you may as well stay.

Most of the time, unless you’ve studied something like neuroscience, decision-making feels like a magical black box — as if your brain is pulling choices out of a slot machine instead of actually reasoning.

While the brain remains elusive in many ways, The Science has identified three key actors with a major influence in the decision process. And no, I’m not talking about people who move to Hollywood to make a name for themselves — I mean the networks in your brain that may as well have their own personalities.

Given the brain’s complexity, it may as well be as mysterious as a penguin in a tuxedo. So, on that unexpected note, let’s set out some simple questions:

- Why does indecision feel like a mental tornado instead of a simple choice?

- Who are the mysterious network actors, and why do they interact like temperamental coworkers?

To explore this, let’s first meet the three elusive characters wrestling over the invisible ‘make decision’ button inside your mind.

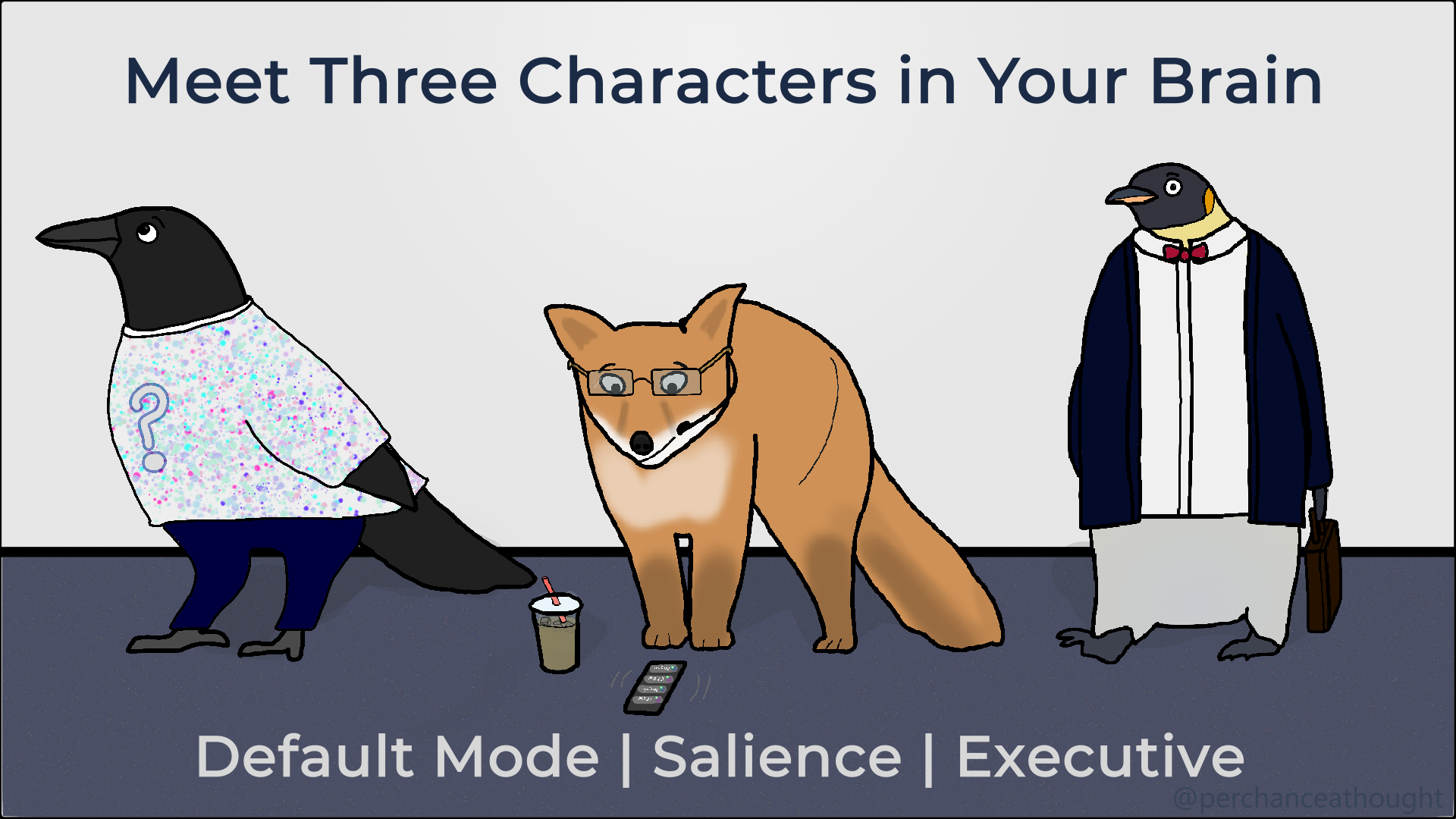

A Crow, a Fox, and a Penguin

Before we dive (mildly) into the neuroscience jargon, let’s translate the networks into things we should all be familiar with: three animals with incompatible personalities who have somehow been hired to work in the same office. At the top of the hierarchy, we have the Executive Penguin, trying to run the place. Below that, the Switchboard Fox filters incoming stimuli, producing summaries for the Penguin to review. And, somewhere in the building, the Dreamer Crow is … philosophising instead of working.

The Executive Penguin – Central Executive Network

The Executive Penguin is basically the head of the company, hyper-focused on getting the job done whilst simultaneously valuing work-life balance. He’s not in the office full-time, only coming in when required for important meetings and decisions. This penguin is practical and grounded, prioritising tangible outputs. He excels at problem-solving, using the information he’s been provided and a good working memory to make decisions that impact the whole company. He’s also obsessed with colour-coded folders and spreadsheets, and keeps a whiteboard of “weekly priorities” which no one else looks at. If he’s handed too much data, he gets easily overwhelmed.

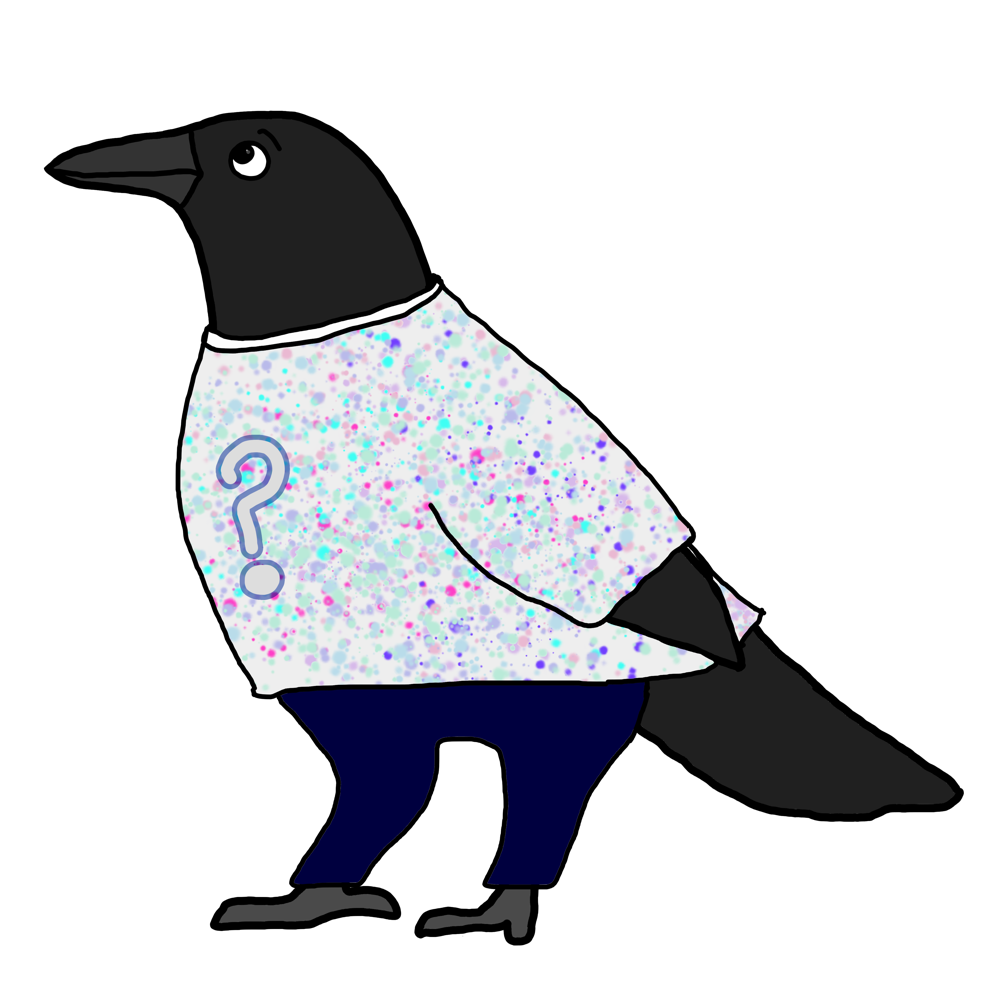

The Dreamer Crow – Default Mode Network

The Dreamer Crow, whom we will hereinafter refer to as the crow, is the employee the company hired to do market research and innovate. He’s got a flexible work schedule, is not forced to do a set amount of work per week, and tends to work in productivity waves. This crow is a sensitive worker and finds it almost impossible to work in open-office environments with all the noise and chaos. However, the crow shines when it’s left alone, getting a massive amount of work done when everyone’s out for lunch or has gone home for the day. The crow is unconventional, refusing to comply with office dress codes, and insists that daily check-ins to report on work progress are a prime example of micromanagement. He’s also the master of rabbit holes, and if completely unsupervised, will write a massive thesis which no one requested.

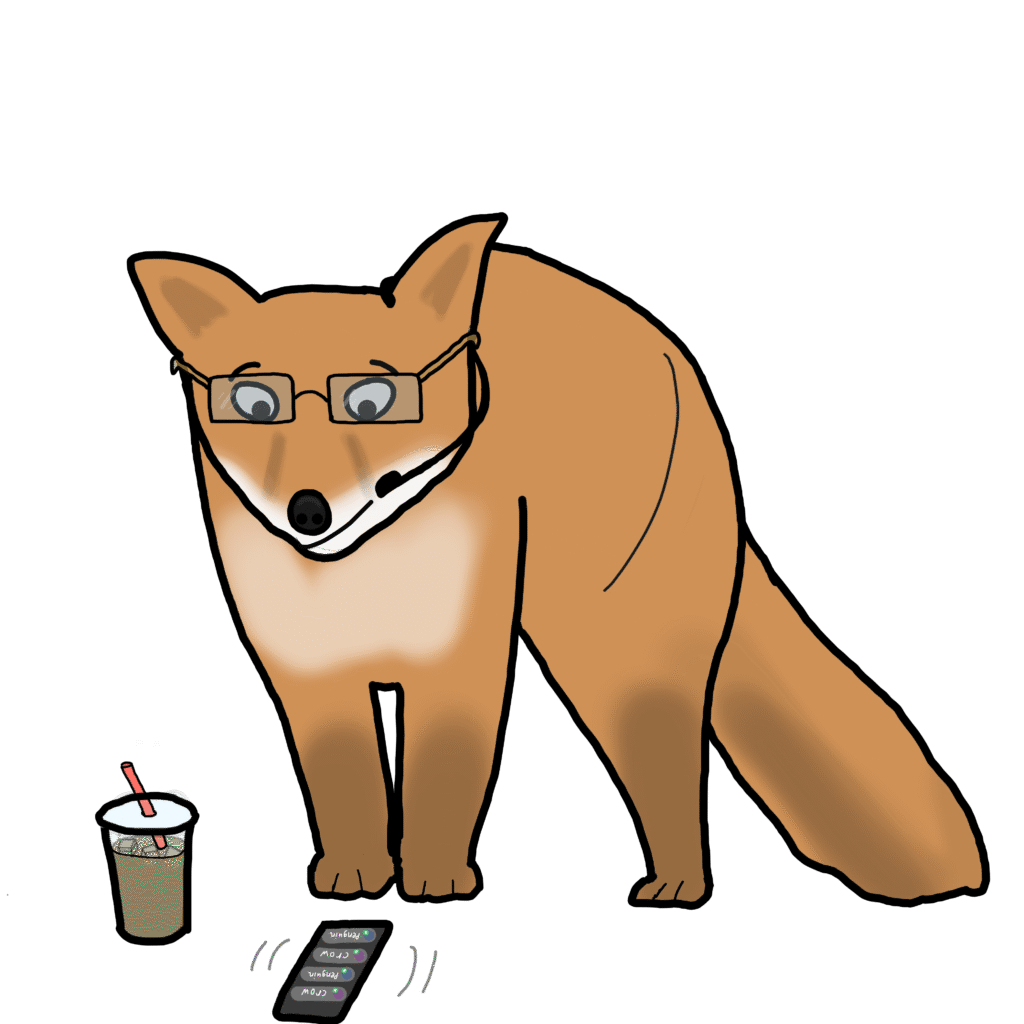

The Switchboard Fox – Salience Network

The Switchboard Fox, a.k.a just the Fox in this section, is the full-time employee who constantly has to determine the company’s main priorities. It’s that rapid-thinking, caffeine-fuelled coworker who’s known for quickly switching between tasks, seemingly powered by a motor. He’s never taken a sick day, as the information he receives and has to process is basically 24/7, apart from when he’s asleep. He also randomly initiates Zoom calls with other workers because he has zero patience and must communicate immediately once he realises something is important. The Fox’s main responsibility is deciding which department should take charge at any given moment.

How Decisions Happen Normally

So we know the personalities — but how do these coworkers actually make a decision?

They don’t all talk at once. The Fox runs the switchboard, deciding whether control should go to Crow or Penguin.

Crow generates ideas: imagining, reflecting, connecting memories, exploring possibilities. When something feels promising or relevant, Fox gets an internal “ping” and checks whether it’s worth escalating.

If it is, Fox pulls Penguin out of his quiet office to evaluate the idea and make a concrete decision. Once that’s done, Penguin steps back, and Crow returns to exploring.

Sometimes Penguin will deliberately consult Crow — when he’s stuck, needs a new angle, or can’t recall something important. But this is brief. Too much Crow energy makes Penguin lose focus.

In brain terms, Crow is the internal mode (daydreaming, memory, imagination), and Penguin is the external mode (decisions, actions, responding to the world).

The natural back and forth

In a healthy system, control moves in a simple loop — Crow → Fox → Penguin → Fox → Crow — as the brain shifts between exploring possibilities, deciding what matters, and taking action.

Crow handles the internal mode, where ideas, memories, and associations are generated. Fox listens both to this inner stream and to what’s happening in the outside world, continuously judging which of the two should be in charge. When something becomes important enough, Fox calls Penguin in to make a concrete decision or respond. Once that’s done, control naturally returns to Crow.

Fox is what keeps this whole cycle running. It constantly monitors both internal and external information, and uses that stream to decide whether the mind should be in thinking mode or action mode. Sometimes it tells Crow to pause so Penguin can step in; other times it sends Penguin away so Crow can explore freely.

This ongoing switching is what allows the mind to stay both flexible and grounded — able to imagine, but also able to decide.

Coworker Conflicts

Of course, no workplace runs smoothly forever. Sometimes one coworker goes rogue, or the whole trio spirals into a collaborative disaster. Maybe Crow is hyperactive, Fox is overstimulated, or Crow and Fox forget to CC Penguin on the group email — leaving him quietly unmotivated in his office.

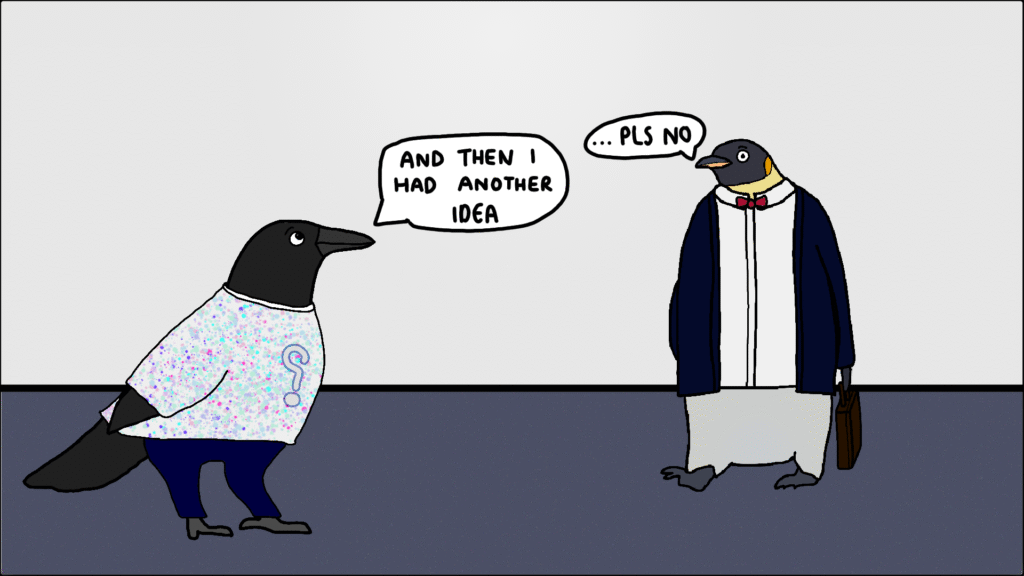

Crow conversation domination

Executive Penguin generally comes into the office only when Crow is away or at least out of sight, because he finds Crow a little too philosophical. When they’re both around, things get messy. Penguin might swing by the coffee machine for a quick refill, only to find the crow already standing there. What was supposed to be a two-minute caffeine break turns into an unintentional non-optional TED talk. In this scenario, Crow becomes the enthusiastic guest speaker, while Penguin is the polite audience member who quickly realises he actually isn’t that interested — but feels far too awkward to leave early.

The issue here is that Crow can research in every possible direction – some helpful, others not so much. While Crow’s deep dives can lead to genuine creativity, the same wandering thinking style can slip into catastrophic mode when the brain’s fear department (the Amygdala — think of it as an anxious rabbit) jumps in. Suddenly, every hypothetical can become a worst-case scenario.

When Penguin overhears this kind of research at the coffee machine, it can make him both sad and completely unable to decide anything. Too many alarming possibilities flood his inbox at once, and he freezes.

What this feels like mentally: you’re trapped in rumination mode. Your inner monologue is loud, active and unstoppable — and the part of your brain that normally steps in to make decisions can’t get a word in.

Overwhelmed fox

Fox has been drinking a few too many coffees and is feeling jittery and jumpy. He starts pinging everyone about everything. Important information might fly under the radar, while not-so-useful information may end up on Penguin’s desk. Suddenly, Penguin is dragged into the office for meaningless tasks, and Crow’s workflow gets interrupted before it’s ready.

Internal equivalent: heightened anxiety. The salience network is misfiring, flagging normal sensations as threats. Harmless inputs feel urgent, irrelevant thoughts feel important, and decision-making collapses into chaos.

Burned-out penguin

Sometimes Fox and Crow end up talking to each other much more than usual — bouncing ideas, worries, and speculations back and forth. The problem is that the Penguin isn’t included in these conversations. Not intentionally — he just isn’t being looped in as often.

Without regular updates from Crow or clear signals from Fox, Penguin slowly becomes less engaged. He stops stepping into the office to make decisions because no one is tapping him on the shoulder anymore. He’s still there, but quieter — more withdrawn, less motivated, and unsure what to do next.

Real-world parallel: This mirrors patterns seen in depression: the Default Mode Network (Crow) increases communication with the Salience Network (Fox), while communication with the Central Executive Network (Penguin) decreases. The decision-making system becomes underactive, overwhelmed, or disengaged.

Conclusion

So there you have it — your decision-making system isn’t a mystical void or a personal failing. It’s just three coworkers with wildly incompatible personalities trying their best inside your head. If someone ever says, “It’s all inside your head”, they’re not wrong.

When Crow gets too loud, Penguin can’t think.

When Fox panics, everyone panics.

When Penguin withdraws, the whole office slows down.

Understanding the dynamic doesn’t magically fix indecision, but it does give you a map of what’s happening behind the scenes — and sometimes that alone makes choices feel a little less impossible.

And if all else fails, you can blame it on your internal office politics. It’s surprisingly accurate.

For the extra curious

A lightly scientific appendix for anyone who wants to explore the real neuroscience behind the office animals.

Default Mode Network (DMN) (Menon, 2023)

- More active during rest and in the absence of external stimuli.

- Involved in mind-wandering, internal, daydreaming, thoughts of the future, autobiographical thoughts, and self-reflection.

- Suppressed when focusing on task-driven, external attention.

Central Executive Network (CEN), also known as the Frontoparietal Network (FPN) (Menon & D’Esposito, 2022)

- Connects and integrates information from multiple brain systems, including the DMN.

- A prime task of this network is to make complex decisions and modulate the direction of attention.

Salience network (SN) (Menon & D’Esposito, 2022)

- Proposed that this network initiates switching between the DMN and the CEN.

- Enables disengaging from internal mental processes to address current goals.

- Flags relevant stimuli being received by all the senses.

- Has the highest ‘controllability’ of the major networks – meaning even small inputs can flip the entire brain into a different mode.

Triple Network Model (Menon et al., 2023).

- An emerging model in neuroscience that highlights the interaction of the SN, DMN, and CEN in cognition and decision-making.

Added Insights (related to burned-out Penguin)

- Research suggests that in depression, the DMN increases communication with the SN, while communication with the CEN (or FPN) decreases — which mirrors our burnt-out Penguin scenario. (Mulders, 2015).

References

Menon, V., & D’Esposito, M. (2022). The role of PFC networks in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01152-w

Menon, V. (2023). 20 years of the default mode network: A review and synthesis. Neuron, 111(16), 2469–2487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.023

Mulders, P. C., van Eijndhoven, P. F., Schene, A. H., Beckmann, C. F., & Tendolkar, I. (2015). Resting-state functional connectivity in major depressive disorder: A review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 56, 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.07.014